- Abstract

The aim of this article is to analyze the functioning of the Clean Air program after the reform implemented on March 31, 2025, with particular emphasis on its impact on the contractor market and the efficiency of financing and quality control mechanisms. An assessment was conducted of institutional changes (role of public operators, prefinancing system), structural changes (unit cost table, ZUM list), and economic changes (company cash flow, payment bottlenecks, administrative costs). The analysis was based on data from NFOŚiGW, WFOŚiGW, official communications, and industry materials from the 2024–2025 period. As a result of the reform, the number of applications in Q2 2025 fell by over 80% year-on-year (from 78,300 to 11,200), causing a temporary reduction in orders and increased uncertainty among contractors. At the same time, quality mechanisms were strengthened (mandatory EU/EFTA certificates and test reports for heat pumps, central ZUM list), and the public control system limited abuses previously estimated at approximately 600 million PLN. However, growing payment arrears exceeding 1.2 billion PLN were identified, along with divergent settlement practices among the 16 WFOŚiGW, negatively affecting the sector’s financial liquidity. Research results indicate that the reform increased transparency and security of public spending, but simultaneously transferred part of the administrative and financial burden to micro and small contracting enterprises. The authors propose a set of improvement recommendations: standardization of verification procedures, introduction of staged bridging payments, and cyclical standardization of project and evidence documentation. The findings obtained may serve as a basis for designing subsequent stages of thermal modernization support policy in Poland, toward a balance between control, economic efficiency, and contractor market stability. [1]

- Introduction

“Clean Air” is today the largest energy modernization program for single-family buildings in Poland—with the ambition of simultaneously reducing energy poverty, emissions, and heating bills. Its structure combines three dimensions: public policy (subsidizing eligible costs), building engineering (from building physics to HVAC systems), and a massive, dispersed contractor market with highly variable quality culture. At this scale, individual “incidents” cease to be isolated cases; they are side effects of economic incentives and imperfections in verification processes—from equipment selection, through documentation, to settlements. In the new version of the program (year 2025), significant safeguards were introduced: stricter equipment eligibility (ZUM List), public operators on the side of municipalities and WFOŚiGW, and unit cost tables designed to anchor valuations in market realities. Simultaneously, the program faces fundamental threats such as anchoring offers to maximum indicators, bundling of quasi-services, and outsourcing of investor decisions to intermediaries. At the intersection of law, technology, and market practices, mechanisms of abuse arise—often formally correct but substantively questionable. This article views the program as a system: it identifies typologies of abuse (apparent implementations, cost inflation, model substitutions, non-compliant execution), breaks down into prime factors the four most vulnerable categories (exterior doors, heat pumps, PUR insulation, wall-mounted heat recovery units), and shows where—despite reforms—gaps remain in oversight and data. The conclusion consists of systemic recommendations that can improve the program.

- Program Architecture and Incentives

The program is coordinated by NFOŚiGW and operationally serviced by 16 WFOŚiGW and—after the reform—public operators (municipalities and WFOŚiGW themselves). From March 31, 2025, applications opened in the new version, with financing including from the Modernization Fund (10 billion PLN), with operators leading beneficiaries “from A to Z.” Hard “quality filters” are the ZUM List (for heat pumps and selected materials) and unit cost tables (references for cost assessment in settlements). Prefinancing (advance payment) was limited and linked to additional conditions—this is intended to limit advance-related abuses. These solutions organize the process ex ante, but with dispersed tasks and mass applications, niches still exist for creative cost estimates and quality “shortcuts.” [1], [2]

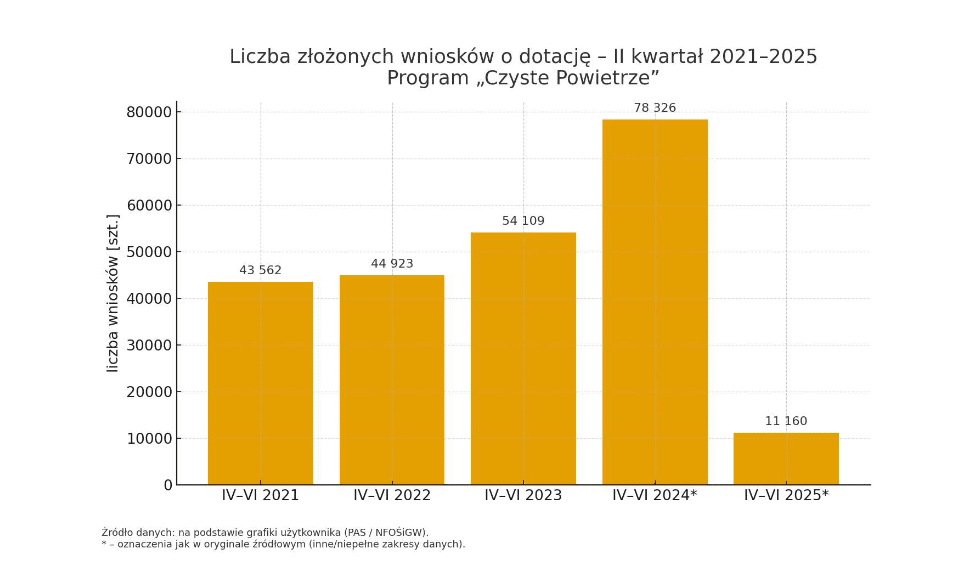

It should be noted, however, that after the program reform, the number of submitted applications significantly decreased. The drop in applications has several overlapping causes. First, regulatory shock: the suspension of applications at the end of 2024 and the start of the new version on March 31, 2025 created an uncertainty effect among beneficiaries and contractors. Second, tightening of rules (including mandatory heat pump listing on the ZUM List, stricter documentation requirements, design/audit for ventilation) raised the entry barrier and eliminated some “easy” implementations. Third, limitation of prefinancing (advances only through the operator, requirement to attach contracts, maximum three) worsened liquidity for smaller companies and reduced aggressive “we’ll handle everything” acquisition that previously pumped up volume. Fourth, the unit cost table lowered the profitability of creative cost estimates, so some entities withdrew offers or redesigned them, temporarily weakening supply. Fifth, negative media noise around abuses undermined trust and led some households to postpone decisions. Finally, there’s a structural factor: saturation of “early” segments (simplest replacements already done), higher own contribution for more expensive, complex modernizations, and cost-income pressure on households—all cumulatively lowering willingness to apply in the short transition period. The chart shows the number of applications submitted in the “Clean Air” Program. [4]

In Q2, the number of applications grew year-over-year from 43,562 (2021) to 44,923 (2022, +3%) and 54,109 (2023, +20%), reaching a record 78,326 in 2024 (+45%). In 2025, there was a sharp plunge to 11,160 units (-86% y/y). This decline is the result of the suspension of applications at the end of 2024, the program “restart” on March 31, 2025, and stricter requirements (ZUM List, cost tables, prefinancing only through operator). Data for 2025 is marked with an asterisk (partial/different aggregation), but the trend of demand collapse is clear and transitional in nature.

One more aspect of the new program version is worth considering. In the previous version, everyone could count on some form of financial support depending on their income. In that version of the program, there was a distinction between comprehensive building thermal modernization (reducing useful energy demand by min. 40%) and non-comprehensive thermal modernization, i.e., reducing energy demand by less than 40%. In the segment of the most energy-consuming single-family homes (colloquially: “energy vampires”), the key barrier to accessing support is not the necessity of reducing consumption itself, but the requirement to reduce heating useful energy (EUco) below 140 kWh/m²·year. For a building with EUco = 260 kWh/m²·year and 120 m² area, this means going from approx. 31,200 kWh/year to ≤16,800 kWh/year, i.e., at least ~46% reduction. In stock with EUco of 300–350 kWh/m²·year, the 140 threshold implies over 60% reduction. Such deep effect can rarely be achieved by a single intervention; it requires a cascade of actions: wall and roof insulation, window replacement, partition sealing, often ventilation with heat recovery, i.e., investments of several dozen to over 100,000 PLN. Paradoxically, the highest financial threshold affects households most exposed to energy poverty.

The rigid threshold of 140 kWh/m²·year creates problematic situations: buildings already moderately efficient qualify relatively easily (where “the last 20–30%” is achievable), while the most energy-consuming ones—though environmentally and health-wise most important—drop out at the start. The market responds with a “source first” strategy (e.g., replacing a boiler with a heat pump), which lowers bills but doesn’t meet the threshold and often ends in refusal of co-financing. The result is intervention regressivity: public funds reach the worst stock less effectively, and low emission reduction slows down.

From an instrument design perspective, alternative paths to the absolute threshold are justified:

- Relative path (performance path): qualification after documented EUco reduction of ≥40–60% relative to baseline, regardless of achieving 140 kWh/m²·year.

- Two-stage path (milestones): stage I – building envelope (insulation, windows, air-tightness, basic ventilation), stage II – heat source and installation fine-tuning; tranche payments after reaching milestones.

- Threshold correction by climate zone and typology (year of construction, material, volume) – 140 kWh/m²·year in a colder zone means different effort than in a warmer one.

- Measurement verification based on energy bills corrected for degree-days (HDD) and usage profile, to reward real improvement, not just model compliance.

- “Worst-first” path: higher subsidy intensity, prefinancing, and project support for buildings >250–300 kWh/m²·year, aiming for significant reduction (e.g., ≥50%) and a plan to reach 140 kWh/m²·year within several years.

Implementation of the above solutions should go hand-in-hand with evidentiary rigor (baseline audit, acceptance protocols, photographic documentation with metadata, as-built diagrams) and clear settlement rules. Such arrangement lowers the entry barrier for “energy vampires,” improves program distributional fairness, and accelerates achievement of environmental goals where the marginal effect of each public zloty is greatest.

- Typologies of Abuse – Mechanisms, Not Exceptions

4.1. Apparent (or Quality-Degraded) Implementations

In documents, everything checks out: invoices, protocols, declarations. The problem reveals itself only during post-execution audit: missing safety elements (groups, valves), missing commissioning documentation, non-functional ventilation, “warm installation” only in name. Such cases don’t have to be invoice fraud—it’s quality degradation below program and regulation expectations, while maintaining formal compliance. Warning signs also include serial number inconsistencies with equipment cards and missing photo metadata from installation. In 2024, NFOŚiGW indicated the scale of suspicious contracts (approx. 600 million PLN, on 6,000 applications), which initiated procedural reform. [1], [5]

4.2. Cost Inflation Through Bundling and Quasi-Services

“Packages” (accessories, services, extended installations) raise the co-financing base, though their technical value is questionable. Unit cost tables were introduced partly to keep settlements “tied” to the market—if an invoice clearly exceeds ranges, the institution calls for justification (building specificity/technology) or corrects the eligible cost. The tables themselves are not a price list but a reference point—and they act as a brake on “nightmare invoices.” [6], [7]

4.3. Model Substitutions and Catalog Ambiguities

On paper appears a variant meeting criteria, in practice—a “twin” with weaker parameters (different control version, different heat exchanger, different capacity). That’s why the new program version emphasized eligibility of a specific model (ZUM) and hard documents (card/label, test report, quality marks). UOKiK with KAS and IH showed in 2024 that 94% of checked pumps had formal deficiencies—showing how easy “paper” mismatches with requirements are. [8], [9]

4.4. Process Problems: Powers of Attorney and “Decision Outsourcing”

Takeover of the process by a salesperson limits investor control over scope and price. After the reform, the operator is supposed to be the guide through the procedure, and NFOŚiGW publicly warns against impersonation of institutions and fraud of powers of attorney (“check before you trust”). This is important because some abuses are not so much bad equipment as bad processes and information asymmetry. [10], [11]

4.5. Energy Audit – Abuse and Degraded Quality

Energy audit in “Clean Air” serves as a decision-making instrument: it determines technology selection, hierarchy of actions (partitions/installations), projected energy effects, and ultimately cost eligibility. From a methodological standpoint, it is an expert document that should meet requirements of reliability and validity and be prepared by an independent person with appropriate qualifications. In practice, three classes of phenomena degrading audit quality are identified:

- Conflict of interest – audits performed by entities affiliated with the contractor/seller of a specific technical solution. The result is “audit to thesis”—selection of parameters and work scope to justify equipment purchase, not optimize building energy balance.

- Model and assumption bias: adopting overly optimistic post-execution parameters (e.g., n50, recuperation efficiency, SCOP) without proof of their achievability; using catalog values in laboratory conditions instead of seasonal characteristics for a given climate zone; simplifications of geometry and thermal bridges, leading to systematic underestimation of losses.

- Audit process deficiencies: lack of site visit and photographic documentation, “template” audits copied between objects, lack of data trail (software version, material libraries), inconsistency between bill of quantities and model data.

Subsequently, operational examples of biased practices can be identified such as:

- assuming n50 < 1.0 in a building without sealing plan and without air-tightness test;

- entering heat recovery efficiency ~90% for budget devices without type certificate;

- reporting COP at +7 °C as representative for the season (instead of SCOP);

- declaring Ud for door leaf instead of Ud for the set (leaf+frame+threshold);

- normalizing energy consumption without correction for degree-days (HDD) and usage profile.

Effects of weak audits are visible already at the implementation stage. When a report overestimates equipment potential and omits partition deficiencies, the investor gets poorly selected power and technology: oversized heat source is installed in a building with under-invested envelope. Such arrangement degrades real efficiency, raises operating costs, and doesn’t bring closer to meeting program thresholds. As a result, public money goes to solutions with low “marginal effectiveness,” and the profitability of each zloty spent decreases. The difference between what was promised on paper and what can be proven after work completion ends in corrections, refusals, and longer payment waiting times. Over time, trust also erodes—both on the side of households and financing institutions.

There are certain signals that almost immediately betray a problematic audit. Lack of site visit and photos with metadata (location, date) usually goes hand-in-hand with “copy-paste” description. Too good to be true parameters—like n50 < 1.0 in an old house without sealing plan or recuperation efficiency ≥ 85% without certificate—should raise a red flag. Similarly inconsistencies between audit bill of quantities and cost estimate, confusing indicators (EUco, EF, EP) in threshold justifications, or lack of correction of bills for degree-days (HDD) and real usage schedule. If these elements aren’t logical, the audit result is unreliable.

How to counter this? First—independence and qualifications. The auditor shouldn’t be a contractor or supplier in the same investment, and registry entry should depend on verifiable competencies and track record. Second—methodology and evidence: mandatory site visit, table of key assumptions (U, ψ, n50, set temperatures, heating schedule, climate file), data trail from software used, and complete photo documentation; for high subsidies—air-tightness protocol (blower-door) or at least spot/smoke tests. Third—smart system validations: automatic rejection of extreme parameters (e.g., above-average SCOP without source document), and normalization on real data: if bills from 2–3 years are available, they should be corrected for HDD; deviations greater than ±15% relative to model require explanations. The whole should be closed by oversight with real consequences: random checks of high-risk audits, and with recurring deficiencies—sanction gradation from warning to temporary suspension or exclusion from registry. Thanks to this, audit again becomes a tool for rational selection of actions, not just formal justification of purchases.

- Categories of Elevated Risk – Technical-Market Analysis

5.1. Exterior Doors

Regulatory background. From WT 2021, heat transfer coefficient U ≤ 1.3 W/(m²·K) is required for doors between heated and unheated zones; interpretatively this applies to the set, not just the leaf. In practice, there are still offers where the declaration refers to the leaf alone or “marketing” variant, artificially inflating “energy effect.” Here, insight into product card and measurement methodology is useful—and verification whether the offer includes threshold/hardware/seals, which affect Ud in real arrangement. In 2025 unit cost tables, a reference for door joinery appears (per m² level), facilitating assessment of market pricing. [6], [12], [13]

Potential risk areas are:

- “Warm installation” monetized as specialist service, though actual material and work effort may be moderate.

- Lump sums for masonry finishes without bill of quantities.

- Ud declarations without specifying that it applies to the set.

For door installation, attention should be paid to product card (Ud, set definition), description of installation technology and materials used, basic bill of quantities for finishes.

In public debate about program abuses, the symbol became “famous doors”—publicized cases of settlements exceeding 40–43,000 PLN for replacement of one leaf with installation, which illustrated the gap between real market cost and offer practices in the previous program version. In response, a unit cost table was introduced organizing settlements including for door joinery: recommended eligible cost was set at 2,500 PLN/m², and subsidy rates at 1,000/1,750/2,500 PLN per m² (respectively for basic, elevated, and highest level). [14]

5.2. Heat Pumps

From June 14, 2024, only pumps with test report from accredited EU/EFTA laboratories or with one of European quality marks (EHPA Q, HP KEYMARK, EUROVENT) are permitted on the ZUM list; this will be further tightened in the transition period. This is a reaction partly to results of UOKiK/KAS/IH inspections (94% formal non-compliance in checked sample), which revealed serious documentation deficiencies in the market of imported equipment. In the new program version, positive ZUM listing is not an “option”—it’s a condition of model eligibility for co-financing.

Potential risk areas are:

- Power selection without audit (oversizing → higher CAPEX, worse modulation), lack of hydraulic design and bivalent point.

- Accessory bundling (buffers, groups, controls) with margins hidden in lump sums; lack of clear diagram and component list.

- Commissioning/warranty settled as “packages” without clear scope (protocols, setting parameters, user training).

In settlement documentation, attention should be paid to ZUM printout with specific model and invoice date, equipment card/label, as-built diagram, commissioning protocol with parameters, accessory listing (indices, quantities, unit prices).

For heat pumps, one more very important aspect deserves attention. In older single-family buildings where solid fuel boilers previously operated, heating installations were designed for high-temperature regime (typically 80/60 °C at ΔT≈20 K) and moderate flows, with emitters of small exchange surface and often gravity systems. Replacing such heat source with air-source heat pump without parallel thermal modernization of partitions and without radiator modernization leads to systemic mismatch. Heat pump achieves highest efficiency at low supply temperatures (approx. 35/30 °C for surface heating or 45/40 °C for oversized radiators) and small temperature differences (ΔT around 5–7 K) and large mass flows. In installation historically adapted to “coal” parameters, supply temperature demand remains high, and standard panel radiators at lowering parameters to 45/40 °C deliver only a fraction of nominal power. Approximate rescaling shows that a radiator selected for 75/65/20 °C may at 45/40/20 °C deliver about one-third design power. The results are chronic underheating in design conditions, forcing ever higher supply temperatures, frequent electric heater operation, and seasonal efficiency (SCOP) drop from values around 3–4 at 35/30 °C to approx. 2–2.5 at 55/45 °C, and in severe frosts even below 2. This phenomenon is accompanied by hydraulic problems: installation designed for ΔT≈20 K requires after transition to heat pump 3–4 times larger flows, which in practice are limited by small approach diameters, throttled thermostatic valves, ferromagnetic contamination, and lack of balancing. Additionally, incorrectly connected buffers cause mixing of supply with return and further boost required supply temperature, lowering COP coefficient and favoring short compressor cycles.

From energy balance perspective, the primary cause of failures is lack of reduction in building heat losses. Objects with high EUco, requiring at design temperature supply around 65–70 °C, won’t become “low-temperature” solely by source replacement. Correct action sequence has integrated character. In the first stage, it’s necessary to lower heat demand through wall and roof insulation, window replacement, and improvement of air-tightness and ventilation organization (preferably with heat recovery), which lowers required supply temperature for given loss power. In the second stage, emission system and hydraulics must be adapted to heat pump regime: increase exchange surface (radiators of larger dimensions, low-temperature convectors with fan assistance, local surface heating), ensure required minimum compressor flows, apply contamination separators and perform balancing. Only against this background is weather curve selected, bivalent point and possible hybrid configuration for extreme frosts. Proper buffer connection as hydraulic separator and limitation of throttling by room valves closes the list of necessary conditions. The conclusion is unambiguous: heat pump is not a simple “insert” for installation designed for high-temperature boiler; without parallel modernization of envelope, emitters and hydraulics, the system will operate unstably, expensively and unsatisfactorily, regardless of the equipment class applied.

5.3. PUR Foam Partition Insulation

Open- and closed-cell foams have different λ, density and vapor permeability, thus different roles in partitions. Key to effect are: thickness after stabilization, insulation continuity (bridges at framing/installations), correct arrangement of accompanying layers (vapor barrier, rafter ventilation) and UV protection.

Potential risk areas are:

- Pricing “per m²” without stated thickness—after implementation a surcharge appears (“turned out 25–30 cm”).

- Lump sums for “preparation” inadequate to geometry and footage.

- Incomplete technical cards (missing λ/density/fire reaction)—makes it difficult to assess solution equivalence.

In settlement documentation, attention is paid to foam technical card (λ, density, fire reaction), thickness protocol (min. random measurements + photo), description of substrate preparation and protections. (It’s worth verifying cost per m² against local competition and ranges from cost tables for partitions—though tables don’t list PUR directly, cost references for insulation give settlement benchmark).

It’s worth noting here certain practices of companies from the previous program edition. Some companies used their own calculators for selecting “thermal modernization packages,” designed to minimally exceed the required 40% reduction threshold while simultaneously maximizing sale of equipment with high margin. Algorithms preferred sets where the central element was a heat pump and photovoltaic installation of questionable quality selection and installation, and “energy storage” was often presented as DHW storage tank—actually a product with relatively low production cost but sold with very high margin. Lack of unified unit cost limits and market references for selected materials favored anchoring prices “to subsidy”: in market practice, PUR foam pricing reaching 700 PLN/m² at declared thickness of 25 cm was recorded, despite real technical value of such scope being disproportionate to price. As a result, “calculators” didn’t optimize building energy effect as a whole (envelope + systems), but optimized subsidy path—selecting means with greatest “leverage” in accounting and margin, not highest marginal effectiveness of EUco reduction. Such constructed incentive led to allocation of funds toward solutions most advantageous in sales for the offeror, but technically suboptimal for beneficiary and program.

5.4. Wall-Mounted Heat Recovery Units

Wall-mounted heat recovery units are eligible cost, but their number should result from ventilation design or energy audit (stream balance, unit placement). From 2025, cost tables directly indicate recommended unit cost for these devices (800 / 1400 / 2000 PLN/unit—depending on support level), and for complete ventilation with central unit—set cost (16,700 PLN). This is an important “safeguard” against multiplying devices without design and “golden drills.” [15]

Potential risk areas are:

- “Selling pieces” instead of system—selection “by eye” to “fit budget,” without design.

- Core drilling priced as highly specialized work, without reference to real labor intensity (wall material, thickness).

- Hiding operating costs (filters) in ambiguous starter packages.

In settlement documentation, attention should be paid to design or audit (stream balance, locations), unit card/label (efficiency, acoustics, automation), installation protocol (opening, seals, power supply).

In the previous program version, wall-mounted heat recovery units often played the role of “boosters” of energy demand reduction: in offer calculators and audits, they were attributed high heat recovery efficiency, allowing “reaching” the comprehensive thermal modernization variant threshold, thus obtaining higher subsidy at lower cost on the company side than in case of heavy works such as external wall insulation. In practice, this meant selling low-quality devices at several thousand zloty per unit, despite their real market value oscillating around ~800 PLN, and multiplying the number of units “by eye,” without reliable air stream balance and acoustic analysis. Energy effect was therefore paper-based: declared EUco reduction resulted from optimistic efficiency and operating hours assumptions, not real building envelope improvement. New rules organize this area: number and location of heat recovery units must result from ventilation design or audit, and unit cost table introduces price references (including ranges for wall-mounted heat recovery units), limiting “to-subsidy” margins and requiring justification of exceedances. Consequently, recuperation ceases to be an easy “virtual” point for the reduction counter, and returns to proper role—an element of system ensuring controlled air exchange, whose selection and pricing must be technically justified and consistent with modernization goal.

- New Program Version from March 31, 2025

The new program version tightened certain program issues through solutions applied below:

- Public operator: from March 31, 2025, only municipalities and WFOŚiGW perform operator roles—this is the central contact and settlement point (end of “private operators”). [11]

- Prefinancing: available only through operator, advance up to 35% and—crucially—conditional on attaching max. three contracts with contractors already at application stage (and other procedural conditions). This makes “advance abuses” more difficult and arbitrary scope modifications.

- Unit cost tables: cost references (e.g., joinery, insulation, ventilation with central unit and wall-mounted heat recovery units) accelerate assessment and standardize practice of 16 WFOŚiGW. [2], [16]

On the other hand, the program update brings new threats such as:

- “Ceiling anchoring” – market may treat ranges as minimum price list (“since it fits in table, cost OK”). Remedy: enforcing justifications for exceedances and transparency of cost estimate items. [7], [10]

- Splitting/dominating with packages – breaking up scopes and adding quasi-services to “close” within ranges or legitimize higher cost.

- Impersonating operators – NFOŚiGW publishes warnings; this is today a real vector of abuse (calls, “visits” with logos).

- Control Methodology and Analytics

Central database linking equipment serial numbers to addresses and contracts allows detecting repeated “settlements” of same equipment, and e-invoices with unified product dictionaries—decomposing cost estimates (equipment/accessories/labor). Cross-verification with ZUM and photographic documentation (geotags, dates) makes assessment of quality and model compliance more real. (Direction is set by current ZUM tools and ex post control practice). [17]

Risk models (outliers vs. cost tables, Benford for invoice items, price clustering per contractor/region) allow stratified sampling selection of investments for control—placing emphasis on high-risk categories and entities, instead of linear control of all. (NFOŚiGW publishes application dynamics and operator Q&A—this is the basis for building scoring). [18], [19]

8. Micro-Examples of Requirements

- Exterior Doors. Contractor declares Ud at level “~1.1″—but applies to leaf. In settlement, Ud of set (leaf+frame+threshold) from manufacturer’s card must appear. If “warm installation” costs as much as doors, institution can compare cost to door joinery reference ranges and call for justifications/bill of quantities for additional works.

- Heat Pump“8 kW turnkey” without model indication and without proof of ZUM listing won’t pass settlement. If it passes formally—it’s susceptible to substitutions. In practice, hydraulic diagram and commissioning protocol with parameters are also needed. At purchase stage, it’s worth verifying whether model appears on ZUM on invoice date. Remember that 94% of checked models had formal deficiencies. [9]

- PUR FoamPrice “per m²” without thickness and without foam technical card are red flags. In settlement—thickness protocol after stabilization and confirmation of accompanying layers (vapor barrier/rafter ventilation), because they determine long-term durability and energy effect. Table ranges for partition insulation give reference point when assessing whether cost doesn’t deviate from market.

- Wall-Mounted RecuperationThree devices “just because” won’t pass common-sense verification—number is defined by design/audit. Comparison with cost table will show whether unit cost 800/1400/2000 PLN/unit (depending on level) was maintained, and if not—why.

9. Systemic Recommendations

- Dynamic reference ranges (medians/quartiles updated cyclically instead of rigid “ceilings”)—limit anchoring offers to maximum.

- Serial and address trail in central equipment registry + ZUM and e-invoice integrations—closes path to double settlements and model substitutions.

- Contractor risk-scoring (frequency of corrections, price deviations, documentation quality) and independent commissioning for investments above value threshold—smarter use of control resources.

- Standardization of contracts and cost estimates (hard breakdown: equipment/accessories/labor/protocol)—less space for “contentless packages.”

- Anti-fraud communication (ongoing): reminding that operators are only municipalities and WFOŚiGW, and link to official lists and helplines—this really “closes” fraud vector.

- “Clean Air” Contractors: Realities After 2025 Reform

10.1. New Rules Mean New Order Economics

The new program version from March 31, 2025 [20] tightened processes and changed risk distribution on the contractor side. The most important change is the role of public operators—municipalities and voivodeship funds perform operator function, not private intermediaries, which translates to different document flow and advance control. For contractors, this means prefinancing goes only through operator and is linked to specific set of formal conditions already at application stage. In practice, this requires readiness for earlier collection of contracts, product cards, model eligibility confirmations, and provides for more “hard” verification before payment of any funds. Expected cost discipline also changes, because the so-called unit cost table became an anchor for assessing market pricing in 16 WFOŚiGW. For reliable companies, this is a plus—fewer surprises at settlements—but also necessity of transparent breakdown of calculation into equipment, accessories and labor with justifications for deviations. From cash flow perspective, companies must reckon with longer time of frozen funds until application for payment acceptance and attachment completeness. Contractors report that only implementation of check-lists (ZUM, protocols, photo with metadata, model markings) and item naming standards allows shortening path and making payment schedule realistic. New rules simultaneously protect beneficiaries against price pressure and fictitious “packages” of services that once inflated co-financing base. From market perspective, changes are consistent with government announcements: clear rules, public operators, stable financing—in exchange for quality proofs and cost control. As a result, entry barrier grows for companies focused on subsidy arbitrage, and contractors with good back-office and compliance procedures gain importance. In longer horizon, this should stabilize margins, but short-term results in less offer flexibility and increase in administrative costs on company side. For clients, this means greater transparency, but often also longer queues, because some smaller entities withdrew from program service. The whole fits into logic of “new” Clean Air, which combines quality safeguards with organizing market practices. Basic framework of these changes is officially described in program documentation and NFOŚiGW/service communications, and operator and prefinancing only through operator are mentioned expressis verbis. Additionally, guides and program Q&A clearly remind about application suspension period (Nov 28, 2024–Mar 31, 2025) and procedure “restart,” explaining transitional volume gap visible in statistics. This information is crucial to place later fluctuations in contractor service demand in proper context [21]. Unit cost table [22] was openly introduced as response to cost inflation and tool standardizing settlement practice between voivodeship funds; public Funds emphasize this in their communications. For companies, this means “ranges” are not price list but reference point and basis for calling for explanations at exceedances. Importantly, document points to financing sources (KPO, FEnIKS), emphasizing requirement of compliance with broader eligibility rules. In this architecture, naturally importance of model formal compliance (ZUM, EPREL) and document transparency grows. Without this, even technically correctly executed works can “get stuck” at verification stage. Hence growing popularity of checklists and commissioning protocol templates expected by operators and WFOŚiGW [23].

10.2. Demand Scale After “Restart” – Plunge, Then Adaptation

In the first quarter of new rules operation (Q2 2025, actually Mar 31–Jun 30), there was a sharp year-on-year drop in application number, translating to plunge in orders for companies [24], [25]. Publicly available industry studies state that in Q2 2025, approximately 11,200 applications were submitted versus 78,300 a year earlier, illustrating scale of “regulatory shock.” In contractor context, this meant crew downtime, supplier deadline renegotiations, and temporary employment reduction. Simultaneously, official program materials signal that after new version application start, some applications in system were in draft status and awaited completion (especially audits and ZUM documents), explaining delayed demand materialization

for works. This is a natural phenomenon with change of evidence regime and transition to public operators.

From company perspective, adaptation involves rebuilding sales funnel—first complete documents and verifications, then signatures, and only at the end installation and settlements. This translates to lower order seasonality and greater cash flow unpredictability at micro-enterprise level. As a result, working capital importance grows and ability to finance “empty” months without inflows. Contractors with larger administrative backup adapt faster to requirements, which in short term increases market concentration. It’s worth adding that the program itself and central fund communicate stable financing (KPO, FEnIKS, as well as Modernization Fund), so demand didn’t disappear—it rather changed rhythm and requirements. This dichotomy: strong long-term demand versus transitional procedural bottlenecks—well explains why contractors simultaneously talk about “collapse” and “queues in preparation.” Therefore competitive advantage becomes ability to guide client through formalities faster than market. Contractor who delivers complete document package with offer has greater chance of maintaining liquidity and installation crew rotation. Data about plunge and subsequent “rebound” after several weeks was published in numerous industry services and program communications. Conclusions are consistent: volume drop in Q2 2025 was real and resulted from convergence of application suspension, restart, and raised formal requirements, but doesn’t determine long-term task supply [20], [21], [26].

10.3. Abuses and Industry Reputation: “600 Million” Effect

End of 2024 brought loud NFOŚiGW communications about suspicions of abuses for approximately 600 million PLN covering about 6,000 applications, which became impulse for tightening rigor in 2025 [25], [27], [28]. For honest contractors, this was “chilling effect”: client caution increased and decision paths lengthened, while simultaneously institutions began requiring more granular evidence. From market perspective, these events cleaned out some “subsidy” business models based on formal arbitrage and inflating package items. Government and industry service communications clearly indicated notifications to prosecutor’s office and close cooperation with law enforcement. Image-wise, this affected entire sector—from joinery to HVAC—without distinguishing reliable from unreliable. Therefore, proactive trust-building became crucial: transparent specifications, access to product cards, photos with metadata, and commissioning protocols that “defuse” suspicions at offer stage. In 2025, border and product controls joined anti-abuse regime, further sealing equipment market. In systemic terms, it was precisely “600 million effect” that became argument for hard ZUM list, requirement of tests in accredited laboratories, and consistent operator policy. From company perspective, this means change in contracting: less sales rhetoric, more hard attachments at start. Trust rebuilding also requires proper communication about cost table role—not “official price list” but reference tool protecting beneficiary and standardizing decisions of 16 funds. As a result, honest companies find themselves in better competitive position, though must bear higher administrative cost. For sector, it’s also important to inform clients that operators are municipalities and WFOŚiGW, not private brands impersonating institutions, limiting phishing vector “as operator.” This entire block of changes is confirmed by NFOŚiGW communications, economic media publications, and industry services. Conclusions are consistent: without strengthening rigor, reputational erosion could become entrenched; with strengthening—quality grows, but also entry threshold and compliance cost on contractor side.

10.4. ZUM, Controls and Document Logistics, and Guidelines

After reform, it became indisputable that model eligibility MUST result from ZUM list and/or meeting technical conditions (test reports from accredited EU/EFTA labs, selected quality marks) [29]. UOKiK, Trade Inspection, and KAS increased control pressure, really translating to detention of defective equipment batches at borders. Latest communications say directly: 34 models checked, 32 didn’t meet EU requirements, and total 786 units didn’t reach circulation, illustrating scale of import problem of equipment without full documentation. For contractors, this is signal that “paperwork” isn’t formalism but condition of settlement possibility and avoiding payment withdrawal. Standardization was thus forced: printouts from ZUM/EPREL, efficiency cards and labels, commissioning protocols with key settings (weather curve, heater mode, hydraulic parameters). Additionally, photo documentation importance with metadata (date, location) grows, which resolves doubts “what, when and where” was installed. Contractors who adopted “zero slack in papers” principle report fewer calls for explanations and shorter verification time. On institution side, trend is clear: link ZUM database, control results and possibly e-invoices to close possibilities of model substitutions and double settlements. For companies, this means set-up administrative (back-office) is today strategic resource on par with installation crew. It’s worth remembering that ZUM requirements aren’t one-time—model listing must be consistent with invoice date and catalog parameters. In practice, it’s worth archiving screenshots and product cards in “as of date” versions, because public repositories are sometimes updated. In parallel, cost estimate item naming consistency with cost table is recommended, facilitating WFOŚiGW verification. This “evidence culture” is in 2025 de facto industry norm, not advantage of few. Controls and UOKiK/IH/KAS communications and official program Q&A unambiguously confirm importance of these requirements. Practical conclusion: who has order in documents gets money faster and returns to client less often for “more papers.”

10.5. What Contractors Deal With Daily – Cross-Section of Problems and Amounts

First—liquidity: advance only through operator and only after meeting formal requirements means company “finances” material and labor until document acceptance [20], [22], [26].

Second—equipment selection: each model must have “hard” trail in ZUM/EPREL and complete card and label, otherwise settlement becomes questionable.

Third—ventilation and recuperation: unit number can’t be “by eye” because verification is based on design/stream balance and cost table giving reference ranges for unit costs.

Fourth—joinery and “warm installation”: Ud of set is settled, not leaf; inflated lump sums without bill of quantities raise questions already at assessment stage.

Fifth—naming: different practices of 16 WFOŚiGW incline toward keeping to table dictionaries, shortening correspondence and number of calls.

Sixth—photos with metadata: quick verification of actual installation and work scope (e.g., insulation thickness, duct routing).

Seventh—commissioning protocols: must contain settings and operating parameters, because without this it’s difficult to assess real system readiness.

Eighth—service “packages”: cost table and operator verify justification of individual items, limiting space for quasi-services with disproportionate pricing.

Ninth—deadlines: accumulation of calls for explanations without documentation standard lengthens “time-to-cash.”

Tenth—reputation: echo of 2024 cases makes clients ask about quality proofs more often than before, requiring greater transparency from companies already in offer.

Eleventh—import and compliance: after October UOKiK/IH/KAS actions, risk of hitting “defective” equipment significantly decreased but didn’t disappear, so supply contracts should contain clauses about return/exchange of models not meeting requirements.

Twelfth—fixed costs: increase in administration expenditures (documents person, CRM, archive) is new, fixed budget item for small companies.

Thirteenth—education: contractors more often connect with designers and auditors to prepare complete materials for settlement, not just “installation alone.”

Fourteenth—order selection: some companies resign from atypical cases (e.g., complicated reconstructions) due to risk of exceeding ranges and difficulty of justification.

Fifteenth—competition “outside program”: gray zone still exists, but its attractiveness decreases because lack of co-financing and quality guarantees ceases to compensate risk.

All these elements find confirmation in official program instructions, operator materials, and current voivodeship fund communications about cost table and prefinancing rules.

10.6. Scale of Problem – Approximate Numbers and Magnitude Orders (2024–2025)

In macro dimension, loudest number is approximately 600 million PLN and about 6,000 applications reported by NFOŚiGW to law enforcement at end of 2024, directly triggering rule tightening. In micro dimension, October 2025 brought hard data about 786 heat pumps detained at border and 32 models not meeting EU requirements, showing control is not declarative but operational [20], [25], [30], [31]. From demand perspective, Q2 2025 is approximately 11,200 applications versus 78,300 year earlier—this translates to order of magnitude drop in orders, thus company revenues, if they didn’t enter segments outside subsidy. Simultaneously, government communications about stable financing (KPO, FEnIKS) and operator implementation are meant to restore normal application and payment rhythm in coming months. For contractors, maintaining rotation thus becomes key—more smaller contracts with full documentation is today safer than single large risks. In “sensitive” areas (joinery, wall-mounted heat recovery units, “per m²” pricing), unit cost tables act like slider—make values real and maintain discipline, but require better technical description and bills of quantities from companies. With heat pumps, main filter is ZUM and evidence from tests/quality marks, limiting “paper” parameters and model substitutions. From margin perspective, most is lost on item “packages,” and won is on clear labor, well-described accessories and designs that can be defended against ranges. Approximately, companies report drop in “margin freedom” on extras, but also fewer returns and corrections on fund side—which effectively reduces hidden costs (corrections, downtime, correspondence). All this strengthens premium for order in documents and market shifts toward procedural quality. In background, anti-fraud prevention also works (warnings against impersonating institutions), reducing sales pressure “on shortcuts.” Balance for sector is ambivalent in short term but positive in long term: fewer price anomalies, greater predictability, better equipment level. In total, numbers from official NFOŚiGW, UOKiK pages and WFOŚiGW materials close picture of contractor market transformation 2024–2025.

10.7. How Contractors Can Be Helped

First, standardization of settlement practices among 16 WFOŚiGW branches—through central checklists of item names and examples of correct documents—would shorten verification time and reduce number of calls for supplements [20], [20]–[22], [31].

Second, permanent Q&A and operational handbooks updated in one place (program service) would lower administrative cost on micro-company side that don’t have own legal-settlement departments.

Third, implementation of bridging micro-advances (to 35% limit and with clear checkpoints: complete ZUM → installation → commissioning protocol) would stabilize cash flows without resignation from evidence rigor.

Fourth, public reminding that operators are municipalities and WFOŚiGW strengthens beneficiary resistance to phishing and shortens uncertainty time at offer stage.

Fifth, standardization of cost dictionary from table in downloadable template form (CSV/XLS) would be useful, so companies can generate cost estimates “compatible” with WFOŚiGW dictionaries.

Sixth, developing photo-evidence standard (metadata requirements, minimum number of shots, “must-have” list for each scope) accelerates assessment without need for additional site visits.

Seventh, training paths for installers with emphasis on ZUM/EPREL and commissioning protocol completeness could be organized by operators cyclically online, improving documentation quality “at source.”

Eighth, incentives for contractor–auditor–designer cooperation (e.g., point operator grants for preparing complete document set) would increase share of “collision-free” projects at verification stage.

Ninth, publishing short case studies of approved settlements (anonymously but with real numbers) is worth considering, facilitating pricing calibration and showing “what passes” and why.

Tenth, constant communication about cost table role as reference, not price list, would limit offer anchoring “to ceiling” and strengthen quality competition.

Eleventh, development of electronic “explain” forms for range exceedances (with list of acceptable reasons and attachment fields) would shorten letter exchange.

Twelfth, operators could publish monthly “FAQ from verification” with most common documentation errors, allowing companies to draw conclusions in near-real time.

Thirteenth, further anti-fraud and information actions build demand—the greater social trust, the shorter sales cycles and fewer client resignations mid-path.

Fourteenth, consistent equipment quality and formal compliance controls maintain high market level, which in long term benefits reliable companies too.

Fifteenth, ad hoc liquidity “bridges” (e.g., preferential revolving lines for companies implementing subsidy projects, linked to settlement stages) could accelerate sector stabilization without lowering evidence standards.

These recommendations are consistent with publicly announced program goals, current Q&A, operator role, and cost table application practice.

10.8. Arrears to Contractors: Scale, Causes, Mechanics and Effects

In 2025, growing payment delays in “Clean Air” became one of key problems of contractor industry—both for companies settling prefinancing (advances) and refunds after work completion [32], [33]. Public industry services and media reported in September 2025 about arrears exceeding 1.2 billion PLN and ~43,000 applications awaiting consideration, translating to growing number of protests and contractor environment pressure. In some voivodeships, companies began reporting need to limit business scale or transfer part of orders “outside program” to maintain liquidity. Bottleneck accumulation was contributed not only by rules “restart” from March 31, 2025, but also older backlog from 2023—according to NFOŚiGW communications, approximately 200,000 applications for ~2.6 billion PLN were accepted then but not considered, which “stretched” into following years. In March–July 2025, central fund and WFOŚiGW announced process organizing and payment path shortening, but uneven pace of account “unfreezing” between regions intensified differences in company experiences. As a result, in October 2025 media noted wave of lawsuits and further contractor/beneficiary protests, especially in voivodeship centers (e.g., Kielce). This mixture of factors meant program image and market trust suffered, even if in some voivodeships funds reported payments “without delays.” From micro-company perspective, problem is not just time itself but lack of predictability: when “60 days” for consideration and “3 working days” for payment after acceptance turn into months, each formal correction pushes payment to more weeks. In practice, this means frozen working capital in materials (steel, copper, joinery, insulation) and crew wages, sometimes unbearable without credit lines. Sum of payment bottlenecks intensified with new application number drop in Q2 2025 (period of adaptation to new rules), so many crews for several months simultaneously had fewer contracts and longer waiting for funds from completed implementations. In this context, public operator role (municipalities + WFOŚiGW) turned out dual: on one hand they organize process, on other—their own processing capacities and budget cycles became new “bottleneck.” Directly visible that some delays are systemic (financing rhythm, fund flow between central and WFOŚ, uneven backlog), and some—operational (formal errors in applications, interpretation differences among 16 WFOŚ, incomplete attachments). Only coordinated actions at both levels (rules + operation) can really release payment brake. Industry sources and official public institution communications confirm both scale of arrears and causes and declared remedies.

Arrears formation mechanism is worth breaking down into stages, because this helps understand where money flow “jams”:

(1) Payment application submission → formal completeness verification (contracts, invoices, ZUM/EPREL, commissioning protocols, photo with metadata);

(2) Substantive-cost assessment with reference to unit cost table;

(3) Application acceptance and payment disposition;

(4) Fund transfer to WFOŚiGW and payment to beneficiary/contractor account (prefinancing or refund).

According to official program materials and communications, application consideration time declaratively is approx. 60 days, and WFOŚiGW has 3 working days to make transfer after settlement approval—but only when funds are in fund account. If regional fund doesn’t have transfer yet or waits for budget “window,” even positively verified applications await payment. For years, additional factor was divergent voivodeship practice regarding documentation requirements (item naming, cost estimate breakdown, protocols), generating calls for supplements and resetting deadline runs. In 2025, NFOŚiGW and MKiŚ declared improvements—including reminding funds about 3-day transfer deadline after acceptance and organizing “bottlenecks” in process—but in parallel in media and social channels, criticism grew that implementation is regionally uneven. Simultaneously, public operator launch and prefinancing formalization (advance only through operator, usually to 35%) organized ex ante document verification, which in longer period should shorten assessment time, but short-term added back-office work and lengthened “first cycle” of settlements. Finally—on contractor side, many delays are “self-caused” friction: incomplete photos, missing serial numbers in protocols, model differences versus ZUM, invoice sum errors, description inconsistency with cost table. Where companies implemented check-lists, they report fewer calls and shorter path from submission to payment. The whole arranges into picture of systemic-operational problem, where money “exists” but not always on proper account at right time, and documents aren’t “plug-and-play” [34], [35].

Arrears effects for contractor market are multi-layered. First, liquidity: micro and small companies must finance materials and labor for additional weeks/months, raising financial costs or completely limiting number of accepted orders. Second, personnel risk: with long “holes” in flows, best installers seek more stable conditions, often outside program or in large contractor groups. Third, concentration: larger entities with credit lines and settlement departments gain advantage, potentially weakening local competition and raising average prices outside subsidy ranges. Fourth, formal spiral: each document error triggers calls, sometimes “counter reset,” secondarily intensifying bottlenecks. Fifth, supplier relations: refund delays force deadline renegotiations for steel, copper or joinery; those without negotiated terms bear higher inflation and warehouse cost. Sixth, image: media reports about “billion arrears” attach “institutional risk” label to industry, hindering new client acquisition and lengthening sales cycle. Seventh, defensive behaviors: companies more often resign from atypical, technically difficult scopes (greater risk of corrections/over-ranges), impoverishing market offer. Eighth, going outside program: some smaller orders (joinery, minor modernizations) migrate to market without subsidy, bypassing quality standards and evidence, spoiling environmental effect and hitting companies maintaining program regime. Ninth, formal escalations: lack of unified regional practice results in complaints, and in 2025—also lawsuits directed against WFOŚiGW; this is last “emergency path” for companies that exhausted administrative dialogue. Tenth, uncertainty cost: hard to plan crew schedules and material orders when there’s no certain fund inflow date. In sum, arrears are today main factor suppressing healthy order rotation in sector. Public sources confirm both scale of bottlenecks and growing legal pressure/protests on contractor side and announced remedial decisions on institution side [36]–[38].

What are and should decision-makers do to extinguish arrears? First, in July 2025, NFOŚiGW announced payment application consideration procedure improvement and reminded WFOŚiGW about 3 working days for payment after acceptance—this is important but “final” section of path; equally important is ensuring fund transfer on regional fund side before approvals reach accounting. Second, in communications, theme returns of temporary application suspension and “working through” overdue applications—which on one hand organizes queue, on other causes “holes” in contractor pipelines (necessary compensation e.g., operational micro-advances). Third, industry sources indicate need for central interpretation standardization (item dictionary, protocol templates, photo check-lists) to reduce percentage of calls for supplements. Fourth, from contractor perspective, payment staging would help (e.g., bridging advances after ZUM verification → tranche after installation → balance after protocols), consistent with operator logic [39], [40] and binding percentage limit. Fifth, increasing queue transparency is worth it—even simple online status “where is my application” limits calls and shortens information flow. Sixth, short FAQ cycles from verification practice (most common gaps, good document examples) save weeks. Seventh, “hard” tool remains financing alignment between regions and deadline enforcement—without this, WFOŚ differences will persist. Eighth, anti-fraud thread (warnings against impersonating operators) is also element of extinguishing bottlenecks, relieving institutions from incident handling and unauthorized intermediary verification. Sum of these steps allows “uncorking” system without loosening quality criteria, which is in interest of all parties: state, beneficiaries, and reliable contractors. These directions are reflected in official communications and program Q&A materials, as well as industry discussions.

Most important numbers and facts (2025):

- arrears > 1.2 billion PLN and ~43,000 applications in queue (September 2025);

- genesis in 200,000 applications for ~2.6 billion PLN from 2023 that “spilled” into 2024/2025;

- declared consideration time ~60 days and 3 working days for transfer after acceptance, which don’t always translate to practice;

- visible wave of lawsuits and contractor/beneficiary protests, with regional differences regarding problem scale;

- process organizing by operators and announced improvements in July 2025, but with delayed effect in some voivodeships.

These data and observations are consistent in numerous independent publications [32], [33], [36]–[38].

11. Bibliography

[1] “Abuses in Clean Air program. Suspicious contracts for over half a billion zloty – Clean Air Program.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wazne-komunikaty/naduzycia-w-ppcp (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[2] “New Clean Air with clear rules and stable financing – National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management – Gov.pl Portal.” https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/jasne-zasady-i-stabilne-zrodlo-finansowania–nowa-odslona-programu-czyste-powietrze-juz-wkrotce (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[3] “New Clean Air starts – more support, simpler rules – Clean Air Program.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wazne-komunikaty/2025-03-31-startuje-nowe-czyste-powietrze (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[4] “Clean air: dramatic drop in applications. What went wrong?” https://businessinsider.com.pl/gospodarka/czyste-powietrze-dramatyczny-spadek-wnioskow-co-poszlo-nie-tak/1xlh66r (accessed Sep. 18, 2025).

[5] “Scams for 600 million PLN? Prosecutor’s office notified about ‘Clean Air’.” https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/przekrety-na-600-mln-zl-jest-zawiadomienie-do-prokuratury-ws-czystego-powietrza-7099349881588384a.html (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[6] “We are accelerating application assessment in Clean Air program”, Accessed: Sep. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: moz-extension://ca74a7ce-5241-4c74-a274-caed6c6a947a/enhanced-reader.html?openApp&pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fbip.wfosigw.rzeszow.pl%2Fimages%2FTabela_kosztow_jednostkowych_dla%2520_termomodernizacji_domu.pdf

[7] “News – Voivodeship Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management in Lublin.” https://www.wfos.lublin.pl/aktualnosci/komunikat-w-sprawie-kosztow-jednostkowych.html (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[8] “ATTENTION! FROM JUNE 14, 2024 IN “CLEAN AIR” IMPORTANT CHANGE CONCERNING HEAT PUMP MANUFACTURERS, DISTRIBUTORS AND IMPORTERS – National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management – Gov.pl Portal.” https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/uwaga-od-14062024-r-w-czystym-powietrzu-wazna-zmiana-dotyczaca-producentow-dystrybutorow-i-importerow-pomp-ciepla (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[9] “Heat pumps – first inspection results.” https://uokik.gov.pl/pompy-ciepla-wyniki-pierwszej-kontroli (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[10] “Don’t be fooled – check before you trust! NFOŚiGW warns beneficiaries against fraudsters – National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management – Gov.pl Portal.” https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/nie-daj-sie-nabrac–sprawdz-zanim-zaufasz-nfosigw-ostrzega-beneficjentow-przed-oszustami (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[11] “Your operator – assistance in obtaining Clean Air subsidy.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wez-dofinansowanie/twoj-operator (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[12] to Janusz Markiewicz, “JOURNAL OF LAWS OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND”.

[13] “Warm doors according to WT 2021 – PSB Group – building, renovation and finishing materials.” https://www.grupapsb.com.pl/porady/porada/cieple-drzwi-wedlug-wt-2021.html (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[14] “Absurdities in high-profile program. Hennig-Kloska showed famous doors for 43 thousand PLN.” https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/absurdy-w-glosnym-programie-hennig-kloska-pokazala-slynne-drzwi-za-43-tys-zl-7149516650486400a.html (accessed Sep. 19, 2025).

[15] “Does wall-mounted heat recovery unit qualify for co-financing under Clean Air program? – Clean Air Program.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/poprzednie-edycje/pytania-i-odpowiedzi/co-mozna-dofinansowa-oraz-wysokosc-dotacji/termomodernizacja/13 (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[16] “New Clean Air program”.

[17] “ZUM List.” https://lista-zum.ios.edu.pl/ (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[18] “New Clean Air – three months after opening applications, number of applications and signed contracts growing – National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management – Gov.pl Portal.” https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/nowe-czyste-powietrze—trzy-miesiace-po-otwarciu-naboru-przybywa-wnioskow-i-podpisanych-umow (accessed Sep. 16, 2025).

[19] “SUBSTANTIVE QUESTIONS – OPERATOR WORK”.

[20] “New Clean Air program 2025 – questions and answers.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wez-dofinansowanie/pytania-i-odpowiedzi/nowy-program-czyste-powietrze-obowiazujacy-od-31-marca-2025 (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[21] “Part I – Clean Air Program.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/do-pobrania/poradniki-dla-beneficjenta/podrecznik-nowego-programu-czyste-powietrze-obowiazujacego-od-31-marca-2025-r/czesc-1 (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[22] “Unit cost table – useful tool in Clean Air program | Voivodeship Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management in Warsaw.” https://wfosigw.pl/tabela-kosztow-jednostkowych-uzyteczne-narzedzie-w-programie-czyste-powietrze/ (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[23] “We are accelerating application assessment in Clean Air program”.

[24] “Scams for 600 million PLN? Prosecutor’s office notified about ‘Clean Air’.” https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/przekrety-na-600-mln-zl-jest-zawiadomienie-do-prokuratury-ws-czystego-powietrza-7099349881588384a.html (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[25] “Abuses worth 600 million PLN in “Clean Air”. NFOŚiGW goes to prosecutor’s office.” https://energetyka24.com/klimat/wiadomosci/naduzycia-warte-600-mln-zl-w-czystym-powietrzu-nfosigw-idzie-do-prokuratury (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[26] “New Clean Air with clear rules and stable financing – National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management – Gov.pl Portal.” https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/jasne-zasady-i-stabilne-zrodlo-finansowania–nowa-odslona-programu-czyste-powietrze-juz-wkrotce (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[27] “Abuses in Clean Air program. Suspicious contracts for over half a billion zloty – National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management – Gov.pl Portal.” https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/naduzycia-w-programie-czyste-powietrze-podejrzane-umowy-na-ponad-pol-miliarda-zlotych (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[28] “Abuses in “Clean Air” program – suspicious contracts for over half a billion zloty | News | News | Clean air 2025 – up to 170,000 PLN co-financing for thermal modernization.” https://www.czystepowietrze.eu/aktualnosci/naduzycia-w-programie-czyste-powietrze-podejrzane-umowy-na-ponad-pol-miliarda-zlotych (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[29] “Heat pumps – joint actions of UOKiK, IH and KAS.” https://uokik.gov.pl/pompy-ciepla-wspolne-dzialania-uokik-ih-i-kas (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[30] “UOKiK, IH and KAS detained 786 heat pumps not meeting EU requirements – enerad.pl.” https://enerad.pl/uokik-ih-i-kas-zatrzymaly-786-pomp-ciepla-niespelniajacych-wymagan-ue/ (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[31] “Annex 2 to PPCP | Enhanced Reader.”

[32] “Delays in subsidy payments from Clean Air. NFOŚiGW spoke out – Gramwzielone.pl.” https://www.gramwzielone.pl/walka-ze-smogiem/20307547/opoznienia-w-wyplatach-dotacji-z-czystego-powietrza-nfosigw-zabral-glos (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[33] “Billion zloty arrears in Clean Air program! How does government explain situation? » Thermal Modernization.” https://termomodernizacja.pl/miliard-zlotych-zaleglosci-w-programie-czyste-powietrze-jak-sprawe-tlumaczy-rzad/ (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[34] “Prefinancing | Knowledge base | Clean air 2025 – up to 170,000 PLN co-financing for thermal modernization.” https://www.czystepowietrze.eu/baza-wiedzy/prefinansowanie (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[35] “Improvement of payment application consideration procedures in Clean Air priority program – Clean Air Program.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wazne-komunikaty/usprawnienie-procedur-rozpatrywania-wnioskow-o-platnosc (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[36] “Guard from WFOŚiGW and contractor rebellion. In Kielce, Clean Air beneficiaries and independent contractors protest again.” https://swiatoze.pl/straznik-z-wfosigw-i-bunt-wykonawcow-w-kielcach-znow-protestuja-beneficjenci-i-niezrzeszeni-wykonawcy-czystego-powietrza/ (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[37] “Dramatic situation of contractors in Clean Air: protests and lawsuits – GLOBENERGIA.” https://globenergia.pl/dramatyczna-sytuacja-wykonawcow-w-czystym-powietrzu-protesty-i-pozwy/ (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[38] “Delays in payments for ‘Clean Air’. Wave of lawsuits starts – Business in INTERIA.PL.” https://biznes.interia.pl/finanse/news-opoznienia-w-zaplatach-za-czyste-powietrze-rusza-fala-pozwow%2CnId%2C22431677 (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

[39] N. Fund, O. Environment, and G. Water, “QUESTIONS and ANSWERS Operators in new Clean Air program For the care of our beneficiaries”.

[40] “Your operator – assistance in obtaining Clean Air subsidy.” https://czystepowietrze.gov.pl/wez-dofinansowanie/twoj-operator (accessed Nov. 02, 2025).

Dr inż. Maciej Knapik

Designer | Energy Auditor | HVAC Expert | Science Enthusiast. I am 37 years old and have been working in the environmental engineering and sustainable construction industry for over a decade. I graduated from Cracow University of Technology, where I defended my doctoral dissertation titled "Analysis of the scope of thermal modernization and use of renewable energy for a residential building in order to transform it into a low-energy facility." This work gained recognition from the scientific and industry community, and to date has been downloaded over 140,000 times. I combine the experience of a scientist and practitioner – I hold licenses for designing and supervising construction work in the sanitary industry without restrictions. Over the past 12 years, I have completed: • over 50 HVAC projects, • 250 energy audits under the "Clean Air" program, • 180 energy performance certificates, • projects certified in LEED and Net Zero systems. I am the author of 12 scientific publications and recipient of an award for the most frequently cited article. My works have been cited over 100 times. I regularly appear as a speaker at conferences, expert in webinars, and active member of international initiatives related to passive construction (iPHA). For my activities, I received the title of Personality of the Year in the "Science" category. Beyond my professional and scientific activities, for years I have passionately shared knowledge – providing tutoring in mathematics, chemistry, and physics. Over 100 of my students have achieved significant academic success, which for me is an equally important achievement as scientific awards. My goal is the further development of sustainable construction in Poland and implementation of modern technologies that contribute to reducing building energy consumption and real savings for their users.